Cover for the most recent album Wa Ma Khufiya Kana A’atham (2013) by Bahrainian oriental metal band Narjahanam

Metal music has gone global. It is a fact that is recognized by most fans and followers of this genre of popular music. Many documentary films, academic books, and media features have documented excitedly the globalization of metal music tracing it to the farthest corners of the globe.

One of the regions in which metal music has thrived in the past decade is the Middle East. Following the explosion of folk metal—a variety of metal music in which folk tunes, instruments, and themes are fused with conventional metal music—in European metal scenes some 15 years ago, many Middle Eastern bands have attempted to create their own version of folk metal. The term “oriental metal” has hence entered metal nomenclature to refer to bands that incorporate “oriental” sounds with metal music.

To be sure, the adjective “oriental” in “oriental metal” may not only refer to the Middle East; it is sometimes extended to South, East, and Central Asia, but I have the sense it is more synonymous with the “Near East” than the “Far East.” At any rate, I would like to limit my brief discussion in this post to folk metal originating from the Middle East (including North Africa) or folk metal made by musicians with Middle-Eastern origins but living in Western countries.

Of course not all metal music made in the Middle East is oriental metal. Many bands prefer to stick to the traditional genres of metal music (such as heavy, death, doom, or black metal) without mixing them with “oriental” sounds. If they would like to express something related to their cultural environment, they may do so in the lyrics. For example, Syrian band The Hourglass write lyrics inspired by Syrian contemporary literature, but they play traditional heavy metal.

The first band that is generally credited with pioneering oriental metal is Orphaned Land from Israel, which released two monumental albums in 1994 and 1996 (Sahara and El Norra Alila respectively), in which they blended Jewish, Arab, and Islamic music and themes with death metal. This trend was taken up in the late 1990’s by bands like Melechesh, which originated from Israeli-occupied Jerusalem and Bethlehem but then relocated to the Netherlands, and Mezarkabul (a.k.a Pentagram) in Turkey. The past decade has witnessed the emergence of tens of bands from Arab countries which followed in the footsteps of Israeli bands in a very rare cultural exchange between the two warring sides, who usually exchange bombs and hatred rather than musical influences.

The opening track “Find Your Self, Discover God” from Orphaned Land’s second album El Norra Alila

You might be well aware of the notion of Orientalism, which signifies how a monolithic, imaginary picture of the Middle East was constructed in the West. The “Orient” was the “Other” against which the “West” defined itself and on which it projected everything that it wished to stand against. Irrationality, exoticism, laziness, sexual lust, misogyny, violence, etc. were all antonyms of the self-image of the “Western civilization,” and hence they belonged to the “Other;” that is, the “Orient.” These projections—as late Palestinian-American writer Edward Said argued in his magnum opus Orientalism—were implicit in the European colonialist project of subjugating the East. Surely not all works of art, literature, and science by Westerners about the Orient are Orientalist in definition (even during the heydays of colonialism), but a significant number of them display some common characteristics that justify assigning the label “Orientalist” to them.

The problem with oriental metal—at least a great part of it—is not that an imaginary, monolithic picture is being projected on it, but rather is that it is conforming to such an image or defining itself according to it. If you listen to oriental metal music or see its artwork, you won’t miss the obvious Orientalist imprints it carries. For example, see the following oriental metal album covers:

The cover for the album Tales of the Sands (2011) by Tunisian oriental metal band Myrath, which was preceded by an album titled Desert Call (2010)

The cover of the compilation album Oriental Metal released by Century Media in 2012

If you were a lover of oriental cuisines, you might be able to see that these album covers seem as if they were taken from a Middle-Eastern restaurant in some Western city or a restaurant in some Middle Eastern city that caters for Western tourists. The interiors designs and decorations of such restaurants are faithful renditions of Orientalist imaginations of the East.

The words “Orient” or “East” are used frequently by some oriental metal bands, which shows that some of them self-consciously identify with the notion of “oriental metal.” The conceptual package that usually accompanies the “Orient” in the minds of Westerners is also prevalent in oriental metal. Many songs, album titles, and band names refer to sands, desert, oases, and other stereotypes of the “East.”

To be clear, there is nothing called the “Orient” for “oriental” people. “Oriental” people usually see themselves in terms of linguistic, ethnic, religious, or national identities such as Arab, Muslim, Turk, Persian, Egyptian, Assyrian, etc. There is nothing in common between these peoples (in terms of self-identification) other than the fact that they are collectively seen by the West as constituting an imaginary cultural entity to which it refers as the “Orient.” The “Orient,” in other words, exists only in the minds of Western people. Thus the fact that many “oriental metal bands are labeling themselves as “oriental” means that they are somehow accepting this identity marker and maybe conforming to it too.

“Orientalism” can also be heard in many oriental metal tracks:

“Ma’dabt al Audhama” by Saudi Arabian band Al-Namrood, from their 2010 album Estorat Taghoot (black/oriental metal)

Orphaned Land’s most recent music video “All is One,” which departs from their more original older materials into patent Orientalist themes (progressive/oriental metal)

I would like to point out that I neither claim full knowledge of oriental metal nor do I claim that my statements apply to all bands that I am familiar with, but I can say that this is the case with a significant number of their productions, as you can see from the examples throughout this article. I admit that my evaluation of these examples as “Orientalist” can be somewhat subjective; and hence other people may disagree with me. However, I think there is a case for Orientalism here that one can argue about or discuss.

The question that occurred to me some time ago is why Middle Eastern bands are employing Orientalist themes in their music? Is it because they are primarily addressing a Western audience by their music? Or is it the pressure of their Western labels? Some of them have had their albums released by labels based in Europe or North America, but many others have released their albums independently, yet they too reflect Orientalist motifs. Or has the members of these bands internalized the Orientalist projections of the West to the extent they can’t but see their own cultures through its lenses? I don’t have a simple answer, but it’s likely that all the above factors contribute to some extent.

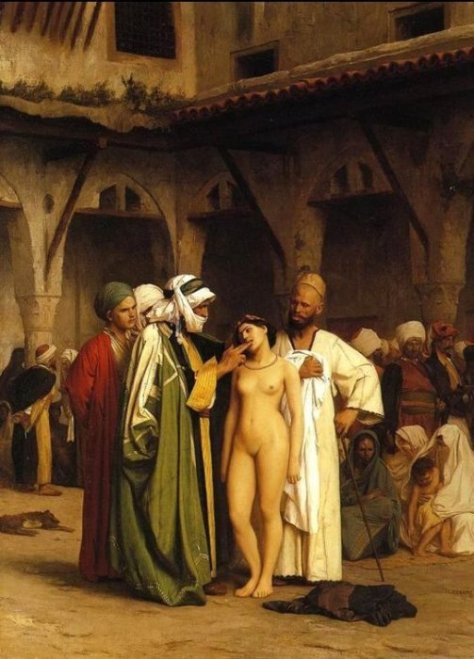

Another possible explanation for Orientalist themes in oriental metal lies not in “orientalism” but in metal itself. Metal music is notorious for blending religious, sexual, and violent themes together; something that is no strange for Orientalism. For example, one of the most common motifs in Orientalist paintings is naked slave girls being sold in the market or displayed to licentious Arab sheikhs:

French painter Jean-Léon Gerome’s “Slave Market” (1866)

“The Slave Market Presentation” by Swiss artist Otto Pilny (1910)

Those who are familiar with metal music can immediately recall images of women on leashes or in cages being displayed in metal videos or even live concerts.

A live footage of British “black metal” band Cradle of Filth (source: livepics.tripod.com)

A still shot from the music video for the song “Progenies of the Great Apocalypse” by Norwegian black metal band Dimmu Borgir from their album Death Cult Armageddon (2003)

Manowar—a well-known American heavy metal band—has notoriously sung:

Woman, be my slave

That’s your reason to live

Woman, be my slave

The greatest gift I can give

From the lyrics of the song Pleasure Slave, Album Kings of Metal (1988)

Oriental metal bands have not yet employed such explicit images and lyrics, but you can get the sense that they are drawing from two worlds which are not far apart from each other: Orientalism and metal.

Themes of power, domination, tyranny, heroism in battle, and hyper-masculinity (contrasted, of course, with subjugated femininity) are also prevalent in both Orientalism and metal music. One of the favorite themes of Orientalist painters was drawing Mamluk soldiers in battle or in full military costume:

A drawing of a Mamluk cavalryman by Carle Vernet (1810)

A Mamluk soldier in armor by Georg Moritz Ebers (19th C.)

In metal, on the other hand, Mamluk soldiers are usually replaced with Nordic warriors:

Album cover of Victory Songs, which was released in 2007 by Finnish folk metal band Ensiferum

Album cover of Eric the Red by Faroese folk metal band Týr (2006 re-release)

Metal is also known for its passion for “enchantment”. The world of metal is heavily enchanted with demons, monsters, and fairies. This certainly reminds one of the “Orient,” which is inhabited with jinn, ghouls, and houris (nymphs). The “Orient” for Western travelers, poets and romantics was an enchanted place where what was not allowed in their own culture (due to the restrictions of rationalism or conservative morality) thrived. The “Orient” was simply the place where “nothing is real and everything is permitted.” The “Orient,” in other words, is some kind of a metal paradise.

I don’t want to judge oriental metal bands and lecture them in cultural authenticity. They have their own artistic agency that they can employ whatever motifs to express their ideas and emotions. Employing Orientalist themes and sounds by itself does not necessarily indicate lack of originality or that the music is unenjoyable. I do enjoy a lot of oriental metal music. Furthermore, one gets the sense that some oriental metal bands are working hard to produce music that is both original and relevant to their cultural environments.

This is not an easy thing given the nature of the global metal music market, where the demand is high for both exoticism and authenticity, which are not usually compatible with each other. Exoticism is largely an imaginary picture created by consumers (mostly Western consumers) and projected on some geographical region; and more often than not this image reflects very little of the true cultural nature(s) of this region. Authenticity, on the other hands, demands that the musician is faithful to their cultural traditions. But when consumers have a very different image of those traditions, matching authenticity with exoticism becomes very challenging to achieve.

I would like also to add that local fans of oriental metal also may find this type of music exotic. It is something completely different from Middle Eastern pop culture and it gives them as well some sense of authenticity.

I haven’t written here all what I have to say about oriental metal. I would really love one day, when I have the time, to elaborate this topic and explore it further. But for now I just hope that this article can generate some discussion among makers and fans of this music as well as cultural critics and academics interested in popular culture in the Middle East, and I hope that some of them pick up this topic and talk about it.

Before I finish this article, I would like to give a couple of examples of bands which are in my opinion making great efforts to produce a more unique and original sound of oriental metal. My favorite example of these original efforts is Narjahanam (Arabic for “fire of hell”) from Bahrain. They have attempted in their two albums to create a distinctive oriental death metal sound by singing in classical Arabic and incorporating apocalyptic themes from Islamic traditions. The following song, “Symphaniyat al-Mowt,” speaks, as far as I can understand the lyrics (which are not published online), of a death or near-death experience:

Another good effort in the world of oriental metal has been done by Egyptian death metal band Sand Aura. Their song “Aljahelia” draws on Arab pagan pre-Islamic history and incorporates a rhyme dedicated to idols (the rhyme was mentioned in an Arabic old book about the idols and then it was popularized by a film about the life of the Prophet Mohammad):

I would like also to note that I haven’t seen an oriental metal band incorporating a subversive political message, except for the early work of Melechesh, which used Assyrian mythology to defy Zionism. Their first EP was called The Siege of Lachish, which celebrates the conquest of the ancient Israeli town of Lachish and the slaughter or enslavement of its inhabitants by the Assyrian king Sennacherib in 701 BC. As Jerusalem Burns… Al’Intisar was the title of their first official album. Al-Intisar means “victory” in Arabic and it possibly refers to the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar II in 587 BC. The inlay of the CD states:

Through these compositions we stab the flag of hell in the heart of god, Jerusalem where we reside, blasphemously with pride.

(source: Keith Kahn-Harris “An Orphaned Land?: Israel and the Global Extreme Metal Scene”).

Oriental metal is still in its beginnings and it is facing several difficulties (lack of infrastructure, persecution by authorities, social pressures, etc.) but I do believe it has the potential to breathe some fresh air into the world of metal, which has become more or less repetitive in the past few years.

Wow! This is very insightful. Being a metal fan from Kathmandu, i can relate to your thoughts on “oriental” music. Back here we call bands with such roots as indigenous metal bands. Pretty cool article.

Thanks llordsauron for your comment. I’m glad that you have found my article insightful. I’m curious about indigenous metal bands in Kathmandu. Do they like these Middle-Eastern bands reflect mostly what the West thinks of their culture or do they find different ways to represent it?

Well, Mohammad, the thing about metal music in Nepal is that we are getting there but we still lack exposure. Last year Behemoth came which is a huge step towards establishing Nepal as the destination for metal music. As far as indigenous metal is concerned i don’t think the west has an inkling to it, let alone have a view. Music is growing and so is our audience. Here’s a link to my review about the new favourite band of Nepal, Underside. Hope you will like it. http://llordsauron.wordpress.com/2014/01/31/welcome-to-the-underside-a-review/

Well, it seems you’re miles ahead of many Arab countries. I don’t think there is any Arab country now where you may have the chance to see Behemoth.

Underside’s style is not exactly mine, but I can say they’re a decent band with decent music. Best of luck for them and metal in Nepal! \m/

http://flavorwire.com/439284/the-challenges-of-diversifying-metal-and-other-heavy-music-scenes/

I enjoyed reading your thoughts on this.

Thanks Nasreen for your comment; I’m glad you enjoyed my post.

Regarding the issues raised by the article you posted, it’s true that in metal there are issues with respect to racism, misogyny, and other forms of discrimination. The problem is that metal has a sense of exclusiveness and elitism, which most of its fans like and appreciate. The challenge for metal, in my opinion, is not to diversify itself, but to remain somehow exclusive, but without racism or misogyny. Is that possible? Maybe!

[…] Fast schon zum Abschluss dieser Blogschau noch einige lohnenswerte Hinweise auf Veröffentlichungen in digitaler oder gedruckter Form. So ist eben die neuste Ausgabe des online verfügbaren IASPM@Journals erschienen. Darin finden sich nicht nur wissenschaftliche Aufsätze über «Sound System Performances and the Localization of Dancehall in Finland» (Kim Ramstedt) oder «Rock Clubs and Gentrification in New York City: The Case of the Bowery Presents» (Fabian Holt) sondern ebenso einige fundierte Artikel zu Aspekten der Metal-Kultur. Um Metal, genauer um «Oriental(ist) Metal Music», geht es auch in diesem Artikel. […]

>The cofrtdenaee flag is not a racist symbol. Don't assume it to be so because some racist groups have co-opted it. Also, got a little political question for you, Dan; what's your opinion of Ron Paul?

That’s a really good and interesting article. Despite not agreeing you on all you say, you made me think about some interesting issues that I haven’t paid attention before. Given that I’ve been writing on a Middle Eastern Metal website, it has made me re-think about some facts that I’ve been dealing with for the last 4 years.

Keep up the good work! Cheers!

Thanks Amir very much for your comment. Sorry that my reply is terribly late, but I would like to know from you which points you didn’t agree with and which website you write in.

Hi Mohammad, nice to meet you! First of all, I want you to know that I liked the article and I agree with most of it. I loved the way you mentioned of Edward Said’s “Orientalism” and the comparison you made between some album covers and West-based Middle Eastern restaurants.

In my opinion, Edward Said’s theories about Orientalism can be applied to Metal music. I totally agree with you when you say that the orientalist themes used by bands are most likely due to the fact that these bands have internalized the orientalist projections of the west. But I don’t agree with the comparison you made between Metal itself and the so-called Orient. Some bands focus their lyrics and artworks on warriors, fairies, extreme masculinity and such issues, but there are too many exceptions to this (probably there are Metal bands which don’t fit in your description than those who do).

Despite the fact that most of the bands tackle their “oriental influences” from Orientalist themes, there are some others that don’t. I recommend you to listen to the Palestinian Rock/Metal band KHALAS, which many plays some Metal covers of traditional Arab musicians such as Oum Kalthoum, Abdel Halim Hafez or Wadih El Safi.

By the way, I recommend you to write more and more about this topic, given that I think that you have tackled something that hasn’t been discussed before. Most analyses about Metal Music in the Middle East only focus on “Oriental Metal vs. Traditional Metal”, on repression by tyrannical regimes and (false) satanism accusations. And myself, as an Edward Said admirer, I’m really looking forward to read more stuff related to this.

Regarding me, I am part Jorzine.com staff. Do you know my website?

[…] they succeed in making something really fresh, much like Orphaned Land’s All Is One, where Orientalist imagery is manipulated to discuss issues that matter to people —- and not just to those in […]

[…] who know me personally or have read some of my posts here (Oriental(ist) Metal Music or “Is God really Dead?”) know me as a dedicated heavy metal fan. For 15 years, almost half my […]